A Bernard Matthews-free Christmas...

*Roaming Wild, the Founding of Compassion in World Farming

To mark the North American release of my biography Roaming Wild, the Founding of Compassion in World Farming, as well as to mark the upcoming festive season I wanted to post this (slightly modified) extract from the book which is all about the two C’s : Christmas and Consumption. I’d love to hear your thoughts on this surprisingly emotive issue around food and Christmas, and of course for those in Canada and America, Thanksgiving. So do ‘Leave a Comment’ below. Friends across the pond you can purchase the book from all the usual places including here and here. (It is currently available on pre-order and will be published on December 1st.) And if you do have a preferred Indie bookstore/bookseller then please let me know the name/s as I’d rather direct interested friends there than to Bezos! Thank you for reading, and please do share this post with those who might enjoy it. And if you do like this post you may also like this one.

Love,

Emma x o x

P.S. Not American? You can buy the book here and here.

P.P.S. for those not in the know Roaming Wild is the story of my grandparents who founded global charity Compassion in World Farming back in 1967, more about them and the book here.

In Eating Animals, Jonathan Safran Foer, novelist and vegetarian activist, examines the multiple strongholds of tradition, family and convention surrounding food, strongholds that –in the West at least – come to the fore on those hallowed occasions of Thanksgiving and Christmas Day…

‘Thinking about eating animals, especially publicly releases unexpected forces into the world. These questions are charged like few others. From one angle of vision, meat is just another thing we consume, and matters in the same way as the degree of consumption of napkins or SUVs … Try changing napkins at a Thanksgiving though … and you’ll have a hard time getting anyone worked up. Raise the question of a vegetarian Thanksgiving and you’ll have no problem eliciting strong opinions - at least strong opinions. The question of eating animals hits chords that resonate deeply with our sense of self - our memories, desires and values. Those resonances are potentially controversial, potentially threatening, potentially inspiring but always filled with meaning.’

This quote resonates deeply. Having grown up in a vegetarian household, as a third generation vegetarian and having never had meat at Christmas time the experience of charge (and a largely negative one at that), and of my family’s Christmas traditions eliciting ‘strong opinions’, was extremely relatable.

I grew up in eighties Britain at a time when a catchphrase thought up by a highly-successful multimillionaire turkey farmer became both common and cute. ‘Bootiful,’ said Bernard Matthews in his thick Norfolk accent on his prime-time TV commercial advertising turkey breast roast, and the phrase entered the nation’s consciousness. (It was for a time as popular as Dell Boy’s ‘Luvely Jubbly’!) Founded in 1950, Bernard Matthews’ farm soon became by far the largest turkey farm in the country, with outposts in Germany and Hungary. The vast majority of the millions of birds on his farms were factory farmed and (bizzarely) Matthews was awarded a Queen’s Service Medal by the Government of New Zealand in 1989.

In 2005 Matthews invented the turkey twizzler, (for those not from the U.K. or not familiar with this 'food product’ it really is worth a look on the link above). The twizzler came to be seen as a symbol of much that was wrong with the modern, processed-meat-heavy diets, in large part due to Jamie Oliver featuring (and critiquing) the food on his TV show ‘Jamie’s School Dinners’.

In 2006 Bernard Matthew’s company hit the headlines again when two contract workers were convicted of animal cruelty after members of Norwich’s Hillside Animal Sanctuary had covertly filmed them playing 'baseball' with live turkeys. Matthews was due a CBE in 2007, but this was postponed due to an outbreak of avian flu at one of his farms. On his death in 2010, the company was sold for £87.5 million.

Today around 10 million turkeys are consumed in the United Kingdom over Christmas, the vast majority of them intensively reared.

An intensively reared turkey’s life is a similarly miserable one to that of the broiler (meat) chicken, and the turkeys share the broiler chickens’ ill-health, including their painful bodily ulcers and burns caused by the overcrowding and often unsanitary living conditions. Like the broiler-chicken, the factory-farmed turkey is prone to broken bones and heart conditions owing to their unnaturally fast, genetically engineered growth rates. Additionally, turkeys have the caveat that given their inherent vulnerability to disease they are perhaps the worst fit of any animal for the factory farm model, so are given more and higher doses of antibiotics than any other farmed animal.

Photo: Anna and Peter Roberts, my grandparents.

Compassion In World Farming’s consistent campaign message has always been that Christmas should be a time of goodwill to all living creatures – not just humans – and each year they asked the public and their supporters to boycott the traditional Christmas dinner for a meatless alternative. Anna’s three cookbooks offered numerous cruelty-free options for the festive table. The Roberts and Compassion hoped more people would decide to celebrate Christmas without cruelty, and the front cover of the December issue of Agscene (Compassion’s campaign magazine) always featured a turkey tale. One year photo of animal activist Gene Baur and partner, putting a nut loaf and roast vegetables into an oven while a pet turkey roamed the kitchen, under the headline: ‘Sanctuary or Slaughter this Christmas?’ with an explanation that ‘Clyde’ was ‘one of the lucky turkeys given a safe home last Christmas by the American group Farm Sanctuary’. (You can see that pic here.)

For many years Peter Robert’s elder brother Frank, his wife Gill, and their sons Barry and Mike had spent Christmas at the Robert’s family home Copse House. But one year, without any explanation, these visits stopped. Barry later said that he suspects this was because his father had had enough of Christmas without turkey. On the journey from Frank’s family home in Birmingham to the Roberts’ home in Greatham, Hampshire, he would warn his children ‘not to ask for meat while they were down there – that was a big no, no,’ that Anna would be ‘cooking vegetarian food, and to avoid the subject of meat altogether.’ At the end of a visit Frank and the family would be given a large box of Direct Foods produce, (the pioneering vegetarian food company that the Robert’s founded and ran with Anna’s sister and brother-in-law, Jan and Bob Howe). Frank would thank Peter and Anna heartily for their hospitality and gift, and then would assure Peter that he’d be visiting the first steak house he saw on the journey home. When Peter had become vegetarian and quit farming, the only job that he then knew how to do, and founded a charity for animals, Frank had thought his younger brother had likely ‘lost the plot.’

But as Frank’s family visits ceased and the three Roberts daughters grew up and had their own children, the Copse House Christmas expanded again and by the nineties we were a close-knit family of 14 with aunties, uncles, cousins and partners jostling for space in the Roberts’s cottage.

We would arrive on Christmas Eve and stay until the 28th. We would arrive to find Peter midway up the 40-foot silver birch at the entrance to Copse House, wrapping fairy lights around trunk and branches; although he was almost 70 he was still as adroit a tree climber as he’d been in his youth.

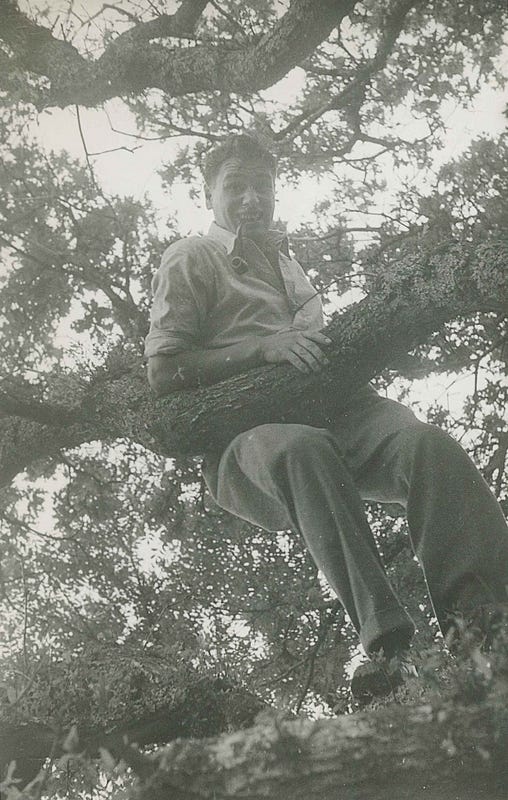

Photo Credit: Peter Roberts, my grandfather, up a tree smoking a pipe in his mid-twenties.

At the kitchen stove one of the three Roberts daughters would be mulling wine with orange juice and brandy, cloves and star anise, and we the children would offload parcels and pile them under the tree, pine needles forming a halo around the base. Gaudy tinfoil decorations and tinsel hung from every surface. In the evening of Christmas Eve we were allowed one pacifying present, and then had to be in bed by midnight, making sure to leave a mince pie and a glass of sherry for Santa.

Anna and Peter gave creatively: pottery wheels, science sets with bunsen burners, basket-weaving kits, watercolours, rune stones, piles of books, knitted teddies, Scalextric, keyboards and a karaoke set. Anna and Peter’s Alsatian, Zara, roams through the paper, tinsel and ribbon. Champagne is popped and more wine is mulled. By early evening we’re at the kitchen table with leftovers, dousing the pudding in brandy, match-ready.

However, new friends, new boyfriends, strangers at parties, only ever really wanted to know one thing about my Christmas. What did we eat? How could the meal be a Christmas meal? What was it like without turkey? The implication, as Jonathan Safran Foer points out, is that ‘the tradition is broken, or injured by a lack of meat’. This specifically sanctioned meal at the centre of the day had, it seemed, come to epitomise the celebration as a whole.

At Copse House the Christmas cooking began shortly after waking up, an Elvis Christmas record was put on, crepe paper table cloth and crackers were laid out, dozens of candles lit. About four hours later Christmas lunch was ready. The cooks were toasted, as were absent friends, and instead of a bird as centrepiece there would be four varieties of nut roast, plus the usual trimmings: potatoes (sans goose fat), boiled-to-death sprouts, carrots, peas, roasted chestnuts, sage and onion stuffing balls, bread pudding made using soya milk, gravy and Jumbo Grills, a product familiar to vegetarians of the seventies onwards– strange, dark brown lumps of TVP, which tasted much better than they looked. There were seconds and thirds. Later Christmas Cake, Pudding and mince pies, brandy snaps and cream. Christmas in a vegetarian household was unremarkable and predictable in the best possible way, full of the same ridiculousness, over-indulgence, and ritualistic merriment as almost any other British home celebrating Christmas in the modern era.

Photo: A Copse House Christmas feature! This is a ‘colour therapy’ lamp from the seventies.

It is worth noting, though, that unlike myself my grandparents had once enjoyed meat. That until 1961 Peter, by all accounts, used to love a Sunday joint, and that both Anna and Peter had grown up with traditional turkey or goose Christmas dinners in their family homes. (Peter and Anna did not turn vegetarian until they were in their late thirties/early forties). Yet later neither Anna nor Peter ever voiced a wish for the more traditional Christmas meals of their childhoods and young adulthood. For them it seemed that the annual Christmas celebration was, to use Safran-Foer’s phrase, ‘enhanced’ rather than ‘diminished’ by the lack of turkey at the family table. The choice not to eat the bird, the bacon, the gammon, ‘a more active way of celebrating’ the season.

Although I’d already read this, it was very interesting to re read today as I’ve been discussing Asda’s whole vegan Turkey with legs! that is available this year, people seems to have very strong opinions on a lump of plant protein!