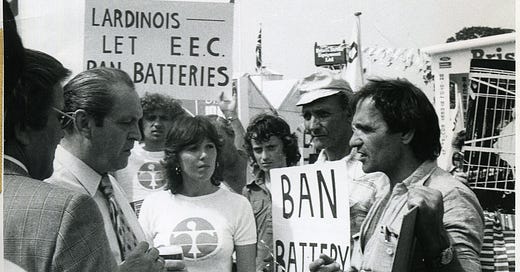

Photo credit: CIWF. Peter Roberts, far right, with comedian and supporter Spike Milligan to his left at a protest against battery farming, 1970s.

The below is an edited excerpt from my biography Roaming Wild, the Founding of Compassion in World Farming. It is the story of Anna and Peter Roberts, my grandparents, and also the founders of global animal welfare charity Compassion in World Farming. This is chapter ten and explores why Nan and Peter, (as I knew them), chose to name their campaign thus. Kim Stallwood who features at the outset of this chapter was Compassion’s second ever full time employee and has been an animal advocate for over 40 years. Kim’s Substack can be found here. Roaming Wild can be purchased from Waterstones here (click & collect or online), from Foyles here and of course from evil Amazon here. Any good bookstore will order it on for you too! Hampshire folks it’s available from wonderful independent bookstore One Tree Books and is also available direct from the lovely publishers here and if you type in CIWF20 at checkout before 30/9/23 you will receive a 20 % discount.

If you are interested in the topic of religion in relation to the animal welfare movement then do check out former CIWF CEO Joyce D’Silva’s new book Animal Welfare in World Religion.

Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others

Kim Stallwood was twenty-one and newly vegan – by his own admission ‘a vegan-gelical’ – when he took a job interview with Peter Roberts, co-founder of CIWF, back in 1976, and he recalls that moment as the first time in his life that he had cause to think deeply about the word ‘compassion’. His mind at the time was, (as he puts it in his own auto-biographical account, Growl), ‘a turbulent and emotional mix of half-baked notions and outraged sentimentalities as regards animal rights and welfare'.

That day beyond the standard interview questions that Peter asked Kim, those ones about work experience, strengths and weaknesses, suitability for role etc. was a question which Kim recalled over 30 years on; Peter asked him if he had ‘a problem with the word ‘compassion’, as some men were 'embarrassed by it?’ Kim swiftly replied, ‘Not me!’ – but he later admitted that he had given such a response only as reassuring answer in order to get the job, and in reality he hadn’t really given the word a great deal of thought. (Kim got the job and worked for Anna and Peter at Compassion for the next two years as National Organizer, he maintains his connection with Compassion decades on and on occasion still works as as a consultant/advisor to the charity.)

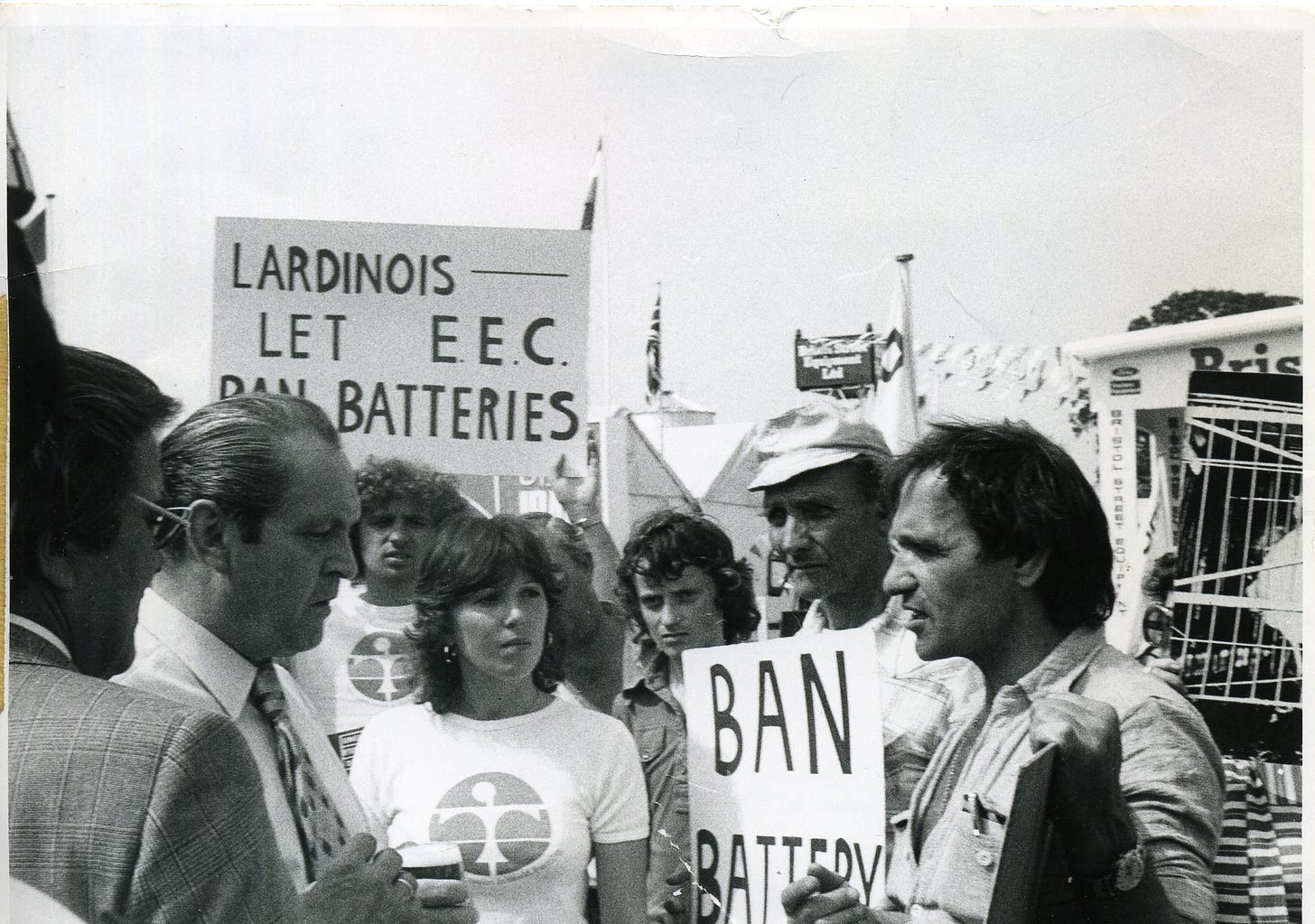

Photo credit: CIWF. Vogue model Celia Hammond in an upscaled battery cage in central London protesting for Compassion in the early 1970s.

Peter’s interview question to Kim was a revealing one, and the Roberts had chosen their campaign’s name carefully; though Compassion in World Farming, is a far from snappy moniker, both Anna and Peter felt it encapsulated their ethos suitably and that this somewhat lofty focus on compassion must be central to their campaign designation. Peter’s interest in exploring the deeper meaning of the word had sprung from his early interest in theology. Though worship was not an especially large part of his adolescence, his parents were both Christian in a loose sense. Peter’s own interest in the mystical can be traced back to the 1940s, a teenage interest which took on an esoteric bent; at 15 he was a member of the Holborn-based Psychic Book Club, and he began practising yoga in his early twenties, roughly two decades before the Western yoga boom of the sixties and seventies. Importantly Peter’s yoga practice was focused on the spiritual rather than only physical aspect of yoga and in activist and writer Jon Wynne-Tyson’s book The Civilized Alternative, Peter had heavily underlined the passage that read: ‘the Asanas of yoga are as exercises meant only as a step to Ahimsa, which is compassion for all life, and Karuna, which is compassion in action.’ Though he did enjoy the material aspect too, and was often found doing headstands, or yogic inversions, against the walls of his family home Copse House. Peter devoured yogic literature and particularly enjoyed Yogi Vithaldas’ book The Yoga System. Vithaldas was one of the key yogis who had brought yoga to the West and was known for being a teacher to violinist Yehudi Menuhin, who also became an early CIWF supporter. It was yoga which led Peter to the sacred Hindu text of the Bhagavad Gita, the 700-verse Sanskrit poem set in a metaphorical battlefield called Kurukshetra, the battlefield an allegory of the ethical struggles of human life. In the Bhagavad Gita, ‘daya’ which is translated as compassion is contrasted with ‘kripa’ which translates as pity. Unlike kripa, within daya there is a lack of otherness between sufferer and empathiser.The Bhagavad Gita had a profound influence on Peter and it was a book he returned to again and again. (In fact when we cleared out the Copse House book shelves following his death I found seven copies of the Gita!)

Peter was to find an affinity with both the Hindu and Buddhist emphasis on compassion. In Buddhism the word translated as compassion is ‘karun’ and in a similar vein to the Hindu interpretation is understood as ‘active sympathy or a willingness to bear the pain of others’.

Photo credit: Roberts Family. Peter in lotus position out the front of Harper Adams agricultural college, 1950s.

While in his early twenties, Peter had read Victorian poet and journalist Sir Edwin Arnold’s eight-book blank verse poem The Light of Asia or The Great Renunciation, which tells the life story of Lord Siddhartha, who eventually became enlightened as Buddha. There is a strong focus in the poem on the necessity of mercy towards ‘the beasts’ and on renouncing ‘the craving for flesh and blood’, with the assertion that all animals ‘crave life and have a will to live’. Arnold himself was a vegetarian and the vice-president of the Bayswater-based vegetarian club that Mahatma Gandhi had founded in the early 19th century. In Buddhist thought, compassion and wisdom are generally viewed as joined roads towards enlightenment with the belief that ‘Truly, you can’t have one without the other’. Thus inspired, Peter often spoke of the necessity of a balance between intellect and judgement, philosophising that intellect without judgement brought arrogance and that the converse brought sloppy sentimentality, and that either was wrong.

Anna’s parents, Fred and Dorothy, like Peter’s, were fairly nonchalant when it came to religion, and though Anna’s mother Dorothy was remembered as being ‘very kind- hearted’ and, as Anna’s sister recalled, was always looking out for ‘waifs and strays and those in need,’ this apparently came from a sense of natural charity rather than Christian obligation. Anna and her siblings Jan and Freddie had been sent to Christian schools ‘because that was what everyone did at the time’, rather than because Dorothy and Fred were great believers.

Thus it was Peter who had introduced Anna to Eastern spirituality, and who a little later was to introduce the whole family to The White Eagle Lodge. The Lodge whose HQ is based in Hook, Hampshire, just a few miles from the Roberts’ former family home, melded various aspects of Eastern spiritualities with the teaching of Christ, as well as with some aspects of Native American belief systems. Though esoteric, the Lodge has piqued the interest of some high-profile followers over the years, including the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle held a firm belief in the existence of the after-life, he researched paranormal activity, and wrote a mostly ignored History of Spiritualism in 1926. Towards the end of his life he was in regular correspondence with the White Eagle, founder, Grace Cooke. It was in fact Lodge member and friend Noel Earle Gabriel who had pushed Anna and Peter to start Compassion.

Photo credit: Roberts Family. Anna and Peter on right with friends at an Ashram in Northern India, early 1990s.

The White Eagle Lodge was founded in Burstow, Surrey, in the early thirties, and more formally in Pembroke Hall, Kensington, London, in 1936. The teachings of the White Eagle Lodge are described as ‘simple and pure ... built on a loving family spirit of helpfulness, kindness and sympathetic understanding of each other’s difficulties, not only the practical difficulties, but the soul struggles.’ The aim of the Lodge’s teachings is to achieve ‘a way of life which is gentle and in harmony with the laws of life, involving the belief that God, the eternal spirit, is both Father and Mother, and that the Son—Cosmic Christ—is also the light which shines in every human heart’. The Lodge’s symbol is a six-pointed star, known as the ‘Christ Star’, which is believed to ‘radiate peace and healing to those in need.’ The Lodge ‘draws on the Ancient Wisdom contained in all the major religions of the world, and its keynotes are love, tolerance and service to all life.’ It combines elements of the religious teachings that already appealed to Anna and Peter, including Hinduism, the New Testament teachings of Christ (ideas like ‘Love in Action’) and aspects of Native American beliefs, especially those linked to Gaia (the ideology that embraces a respect for the Earth). Though in many aspects admirable, the teachings often lose more cynical individuals in light of their method of spiritual delivery: Lodge devotees believe that a deceased Native American named White Eagle imparted his wisdom via psychic messages which he delivered through or to Lodge mother Minesta (AKA Grace Cooke). White Eagle is described as ‘a spokesperson for a group of illumined souls in the inner world known as the Star Brotherhood’ and key amongst his messages is the spreading of ‘light’, a belief in healing, a belief in the afterlife and the importance of following a spiritual path, known as ‘unfolding’. There is an emphasis on meditation and yoga, a belief in astrology, and on pagan and First People’s aligned respect for the natural world. White Eagle was said to promote, via Minesta, a ‘great respect ... for animal life’, and he asked his followers to ‘work for an end to cruelty, and for harmony in and with our natural world’. In a 1969 edition of Stella Polaris, the Lodge’s magazine, Lodge members are encouraged to support Compassion’s work. The article reads:

“Compassion in World Farming ... is working to abolish the needless misery of factory farmed animals and, in the long term, to carry out an educational program for the development in all people of an attitude of kindness and respect for all forms of life.”

The Roberts were official Lodge members for 25 years, although in later years Anna was a much more active member than Peter. Both Anna and Peter throughout their lives devoted themselves to both spiritual and philosophical study with a continued emphasis on the ideal of compassion. At various points they were followers of spiritual teacher and athlete Sri Chinmoy and later of guru Sathya Sai Baba*. However, Peter especially was just as interested in what atheist philosophers and irreligious writers had written on the concept of compassion as he was in any religious scripture or doctrine. He would quote the 18th-century radical French philosopher Voltaire from his essay ‘Of Evil and in the First Place the Destruction of Beasts’ stating: ‘We soon cease to be touched by the awful destiny of the beasts that are intended for our table ... children who weep at the death of the first chicken they see killed laugh at the death of the second,’ or early 20th-century mathematician, philosopher, pacifist and vegetarian Bertrand Russell who noted that: ‘There are certain things our age needs ... It needs compassion and a wish that mankind should be happy ... If you feel this you have a motive for existence, a guide in action, a reason for courage and an imperative necessity for intellectual honesty’. The word ‘compassion’ was at the very centre of the Roberts’ cause and when in the mid-nineties a member of staff at the charity lightly suggested that the charity name perhaps be changed to something more catchy or simple the answer from family members was a resounding NO! Both Anna and Peter felt keenly that the next stage of human ethical development would be, as Peter put it ‘to show that such things as compassion and justice are not restricted to our own species alone’.

Thank you very much for reading! Please do like, share, subscribe, recommend and so on. I appreciate it greatly! And if you are interested in hearing more about Roaming Wild then do enjoy this recent radio interview I did on Petersfield’s Shine Radio. And of course please do check out and support CIWFs continuing and vital work here.

Much Love,

Emma x o x o

*Sathya Sai Baba has in recent times been linked to various scandals and corruptions so it is worth stating here that these crimes were not widely known during the years that Anna and Peter followed Sai Baba and that they were not aware of these accusations of criminal behaviour during their years of following him.