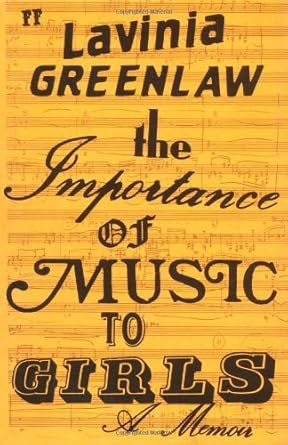

The lovely cover of Lavinia Greenlaw’s memoir (see below).

Many moons ago I picked five of my favourite memoirs and the consequent piece was published in the, now defunct, online magazine Running in Heels. Looking back, almost a decade on I find myself agreeing with my former self - I still find this books very fine indeed! What I noticed too - and which now seems very odd that I didn't notice at the time, is that all the memoirs are writer memoirs. Alas, my taste hasn't changed there either if I were now to add one more and make this list six it would be to include Deborah Levy’s trilogy of reflective essays which begins with Things I don't Want to Know. These three books are broadly focused on her writing life but include too questions around her upbringing in apartheid South Africa (her father was a white anti-apartheid campaigner), her marriage, her separation, motherhood, middle -age, bereavement, birthdays, and Feminism. It's one of the best, most nuanced and profound series of literary essays on the creative process, and how it connects to the rest of life, that I've ever read. (Can anyone recommend others as good? Let me know below if so.) Also, here’s some more Fine Things and here’s my new literary venture

.But back to my original list of five fine memoirs, here you go…

And When Did You Last See Your Father? by Blake Morrison, 1993

Yorkshire-born, South London based poet and novelist Blake Morrison received his widest readership with this memoir centred on the life and death of his father. The book was so popular in fact as to be made into a film of the same name starring Colin Firth as Morrison, ‘every middle-class man’s dream’ as Morrison himself put it. In And When Did You Last See Your Father? Morrison’s dad comes through the pages as a force of nature, at turns charming and affable at others obnoxious and bullying. Throughout, the book probes its title question- the title taken from the William Frederick Yeames painting. Morrison adeptly moves through the stages of his dad’s life as seen through his eyes, continually questioning notions of identity and memory. Who is his father and how will he be remembered? As the wheeling and dealing dad who embarrassed him as a child, or the flawed man he sees as teenager the one who he suspects of cheating on his mother, or else the reduced figure, once boorish, now vulnerable on his deathbed? Morrison’s father’s life is not an extraordinary one- he is a rural GP, a philandering married man, a father who dies of cancer in his seventies- but what makes this story so compelling is the confessional nature of Morrison’s prose; the writers own difficult admission of his ambivalent feelings towards his father.

Bad Blood by Lorna Sage, 2000

The late Lorna Sage prominent academic, critic and specialist in women’s writing in this memoir details the first sixteen years of her life spent in repressed, rural 1940’s to 50’s England and Wales. But more than describing the forming of an individual consciousness Bad Blood is a family saga and at the centre of this family stage stands Sage’s wonderfully, (supposedly), wicked Grandfather from whom she, according to her mother, inherits her bad blood. Sage’s small-town vicar Grandfather is drawn as an impassioned, literary, theatrical figure with a taste for the macabre, (reciting Hamlet’s Yorick speech in the vicarage graveyard), and whose ambitions never come close to being fulfilled and who instead indulges in a life of serial-adultery and heavy drinking. Though he dies when Sage is just nine the figure of her Grandfather looms heavily over her life and the book. Read Bad Blood to enjoy Sage’s evocative portrait of three generations both battling and, occasionally, buttressing one another. This is a quietly triumphant story that closes at the point when Sage just is on the cusp of freedom and autonomy, her limited world about to open outwards. She may be sixteen and pregnant (thought somehow believing herself to be a virgin!) but she is about to begin her academic life in earnest at the prestigious University of East Anglia, having gained a place studying English Literature, despite years of familial suspicion over her love of reading. A gloriously female fulfillment of her Grandfather's thwarted ambitions.

Experience by Martin Amis, 2000

Love or loathe the controversial late writer Martin Amis this memoir, published in 2000 and winner of the James Tate Black Memorial Prize, tells a fascinating tale full of literary gossip and creative rivalry- Amis’ father is the author Kingsley Amis- as well as the impact of trauma; his cousin Lucy Partington was one of the victims of Fred West. And it is this mix of darkness and light which makes Experience such an engaging read. As is often the case in Amis’ fiction-think John Self in 1984 novel Money- the leading man the author paints is a far ways from heroic. Though Amis certainly doesn’t show himself to be a character as despicable as the likes of Self, nor does he shy away from detailing his own failings. Ranging from his neurotic obsession with his own teeth and long line of failed relationships to his near constant anxiety that he receive approval from his cantankerous, often drunk, father. Read this for an at turns sad, absurd and comic slice of angst-ridden literary life.

The Importance of Music to Girls by Lavinia Greenlaw, 2007

Lavinia Greenlaw T.S. Eliot Award shortlisted poet, novelist and librettist takes a less common route in this memoir as she traces the lines of her own history through the medium of music. From a childhood spent learning English folk dance at Cecil Sharp House in Camden, to the joy of making her first mix- tape for a boy she likes, to the discovery of punk and it's consequent electric- blue hair. Greenlaw’s book stands out not because she has an especially dramatic coming- of -age tale to tell but because of the poetry of her prose and because of the evocative lens through which she describes girlhood. For Greenlaw music is universe expanding, a force that allows her to both ‘change the shape of the world’ as well as her ‘shape within it’ it is the ‘external phenomenon’ that allows her as an, ‘unformed thing’ to begin to form, if not complete, herself. As the genre of hedonistic music biographies expands this is a refreshingly subjective tale told from the perspective of an awed and transfigured listener.

Somewhere Towards The End by Diana Athill, 2008

Diana Athill’s autobiography differs from many in that is not just told from the perspective of someone who is aged looking back, (Athill was eighty nine at the time of publication), but is about the experience of ageing itself. And Athill, former distinguished editor and co-founder of the publishing house Andre Deutsch, as well as respected writer herself, is a shining example of how to age well. Though frank about the trials involved in the ageing process as well as, as the title suggests, the proximity of her own death, Athill’s prose is uplifting, her tone cheerful. Somewhere Towards The End is not impressive though because of Athill’s age -as she puts it ‘when you’re old people think you’re wonderful if you mange to eat a boiled egg!’- but because of the vivid details of her day-to-day life and her palpable lack of disregard for the status quo. Within the context of Athill’s era- she was born in 1917-her opinions are strikingly radical. She describes the experience of nearing death as an atheist, her decision to remain unmarried and her lifelong lack of maternal feeling. At one point she flagrantly dismisses the notion of fidelity being right for all describing the desire to be ‘someone’s one and only’ as potentially ‘neurotic, unwholesome and the cause of many ills’. This thought provoking and moving book is one that makes you want to find and befriend the author!

Loved your reviews of five memoirs. They all sound worth a read. How about Maya Angelou?